The Simmons public library was a melting pot of the haves and have-nots, a mixture of homeless people and the wealthy older residents of the nearby neighborhood. An open balustrade went spirally around the circular platform of the library. Many creeper plants with varicolored fragrant flowers added to the magnificence of the nicely curved stone pillars and the wrought iron balustrade of the library. Apart from its wide range of collection of books, its charming ambience attracted people of all ages. It was Amrita’s father’s favourite spot where he spent hours, forgetting the abyss of practical life beneath him.

The library was not very far from their country house. Amrita was born and brought up in this house where the sky was pollution free, brilliantly shining stars hung low from the perfectly clear sky. The giant shadow of the steeple of the church licked the streets and lanes at different point of times of the day. Fleecy breeze during the beginning of the winter cheered up the bordering river into tiny crisp ripples. All these were Amrita’s father’s life.

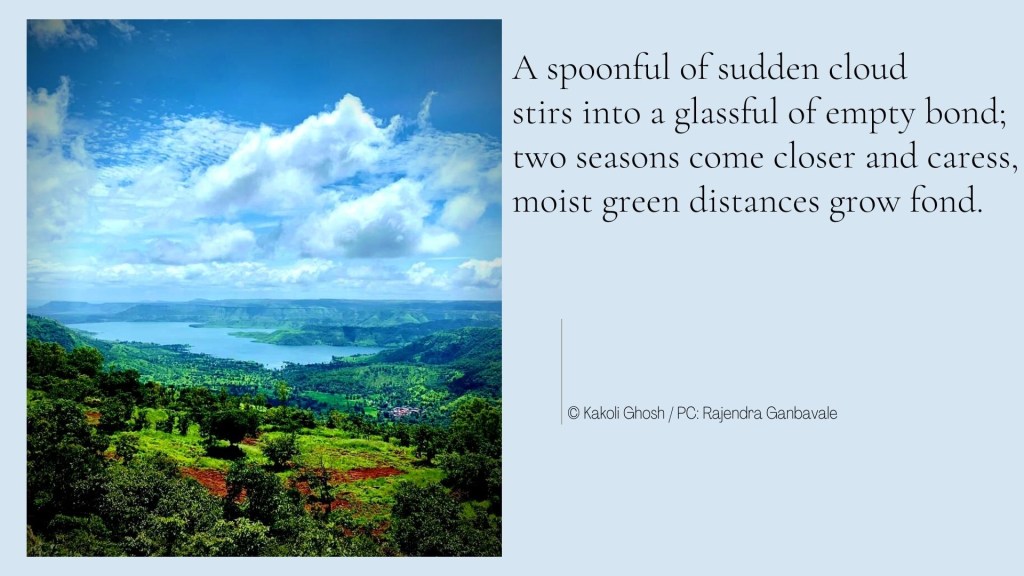

Listening to the twitter of the early birds, inhaling the fresh green breeze blowing from the far-off indistinct hillocks, the peaceful slumber of the unknown weeds in the garden, the whole country house in the vast expanse of the rolling fields encircled by the river, were his means of living.

Amrita’s father lived like a distant fishing boat flowing in a grey riverine horizon, detached from the over-crowded ferries and streamer that crossed the river of daily life. He was a man who was least bothered with the tightly packed schedules and responsibilities of regular life.

Passing most of his time at the Simmons public library, he had developed an unreal world of fantasy around him. After Amrita’s marriage, his house became his only soulmate.

The wooden-pyramid-like dark green roof, the French windows with coloured glass opening into a shaded verandah that encircled the entire house, the crafted pillars skirted by beautiful creepers, the pebble-strewn pathway which made a crunchy sound, resounding every stride, everything related to the house was close to his heart. These almost belonged to the network of his old veins.

With the advancement of his age a thin grey silence had gathered round him like soft most around a half-drowned boulder. He had soaked and wiped off his own loneliness from his forehead, rubbing with the hanky of indefinite time. He started talking with himself, laughed at and wondered about human nature. He quoted well-known lines from famous poems and answered to the dry falling leaves of the autumn. He spent his days remembering the past.

Amrita was accustomed with the glances her father gave, during the matured years of his dementia. Sometimes her father screamed hysterically, sometimes a stream of warm salty tears erupted from his crinkled eyes, dripped down diagonally across his nose and got soaked in his pillow.

A few months ago he could get up staggering, shaking and drooling from his bed and could express his bouts of tantrums on the nurse. But the moment he saw Amrita, he became silent and calm like a whining baby at the sight of his mother. Though none of his uttered words could be understood, his unstable tongue and frayed voice made a terrible trembling sound through his lips trying to sketch a clumsy broken sentence. Only Amrita could decipher those deformed words.Thriving to establish his hallucinations from the Mughal period, imagining himself to be one of the court ministers of some emperor, he struggled to create situations worthy of attention. His subtlety of thought creating confrontation with imaginary enemies, fighting off fearful shadows of illusive warriors, had left him as a left-over from the mainstream of life. Nobody cared to listen to his establishing thoughts and irrelevant ideas.

Amrita managed to come to visit her papa everyday, in spite of her busy schedule as a mother and as a wife, maintaining her responsibilities to her own family. She had been her papa’s doting daughter since her childhood days. “When I will be forgetful, tiresome and weary”, her papa had written in his diary, “when I will drool and will no more be able to count the smiles, laughter, the rhymes or the silly prattles of your childhood that your tiny lips did scatter like the rain blown petals from flowers after storm, your formation of each and every new word like tiny shoots coming to leaves, I will seek the luxury of ripe repose. Then I will be weighed down by countless extinguished suns. Then my empty glance may constrain to hear the jolly splashing in the pond during some golden summer noon; or to see your erratic spellings, scribblings and sketches on the walls of this old house, or may try to catch the intense scent of hundreds of unnamed weedy bushes in our rain-washed garden. In my dreams I may also try to tie back the tender broken bough of the oleander tree where you had tied your little swing desperately.”

The day Amrita was married off and had to leave her old country house, she noticed dry tears at the corner of the eyes of her papa. She had lost her mother during her birth. So she had no memory of her mother except her photograph in a red-bordered white saree, red vermilion mark in the parting of her hair and a big red dot on her forehead.

When the car with Amrita and her bridegroom had started to move, it was early in the morning following the marriage day. At the moment of departure, an intense sadness for leaving her papa in that big old house alone, had clutched her senses. Her father was standing at the doorway waiting to see her off safely and happily. But he was not looking at his daughter dressed in her bridal outfit, anymore. Overlooking the distant bridge to far off dizziness where all ways of their country land ended, he sought the luxury of forgetfulness in his thoughts, as if those happening moments were not real, as if the changeless earth respires only in memories.

Being the only child, Amrita had to take all the responsibilities of her ageing father. That country house was her papa’s lifelong companion. The delicate foot-marks of proceeding time; the seasons coming and going, the sudden splash of the monsoon on the corrugated roofs, the crackling, winding wooden stair to the attic, the broken chair, the wooden almirah full of volumes of complete works of Tagore, Saratchandra Chattopadhyay, Shakespeare and other renowned writers, the sticky bottles of half-consumed forgotten medicines standing at one corner of the almirah, a brass flowervase, two paper weights, some old oil paintings made by her papa absorbing moist solitude, the loosening crevices of the old house, the flowering creeper twisting around the front pillar, the overgrown lawn, the old terrace, everything and every inch of the old house became the best companion and pastime of Amrita’s father. To mend the wooden planks of the ceiling, to patch clumsy cement on crumbling walls, to plant pumpkin seeds in the side patch of land by the kitchen door, making a bed of twigs and branches for the climbing of the creeper plant, enriching the soil with vegetable peels, crushed egg shells, rice starch, used tea leaves, these daily tasks gave him immense pleasure. The delicate green shoots sprawling like cold flames through the earth made him happy. These small things of everyday life gave him a cheerful delight, – as if he belonged to the world of nature and the ageing countryhouse. He remained fully engrossed in keeping and maintaining the old musty flaky house. It was gradually yielding to the engulfing void to time which he could never register in his thoughts.

During winter he lit firewood and created an atmosphere of warmth. Amrita huddled close to her papa and enjoyed the hissing sound of the burning faggots. She kept on noticing the smouldering colours in the dying flames and threw some sweet potatoes in it for roasting. The occasional crackling sounds of peanuts which she also threw playfully into the scintillating cinder gave her tremendous pleasure. The dim wavering light glimmering through the dancing flames before they died out, cast ghostly shadows around, like illusions.

Amrita had to shift her ailing father from this country house to a rented house in Kolkata near her own residence. For the medical facilities and nurse and maid service available in Kolkata, she had to take such a decision, though deep in her heart she knew her papa would feel suffocated within the measured walls of the rented room, where each window opened to the grill or balcony wall of an adjacent house. But he was no more in a condition to revolt or to voice his unwillingness to leave his own countryhouse.

After a prolonged living through a lot of regular medicinal assurances and adult diapers, a blue helplessness of forgetfulness had crept up cold through the network of his swollen veins. He was now living like an extinguished flame, smoky, tearful that can be passed through but can be touched never, in spite of thousand clenches of despair.

His eyes had grown ancient which squinted and strained expecting to see some long known faces at the door. He lay insipid, wrinkled, reduced and disconnected with senses, but on seeing Amrita the layer of dryness on his lips sparkled with a crawling smile. He could recognize Amrita’s smell, her sincere love and could measure the permanent distance between his grey cold helplessness and his daughter’s presence around him. His grandson and son-in-law appeared to him like obsolete connections, which he could not touch anymore.

The salt-caked beige walls of the room, peeling and flaky looked like a barrier to his breath, – a terror overpowering his fading sanity. His eyes perhaps searched for the open sky at his countryhouse. Outside the latticed window competitive ambitious drivers made a cacophony of their vehicles, screeching sounds of sudden brakes from rash driven vehicles for averting sudden collisions creased the silence of the room, the sputtering and jingling of rickshaws in the nearby rutted lane crumbled the endless emptiness surrounding him. Everything appeared weary and wakeful like Macbeth in insomnia.

It was twilight. At the crossing of the lane there was a huge crowd. A solitary silence prevailed among the humming crowd. The nurse could observe from the window. Out of curiosity, she went out to the crossing and reached the gathering. Amrita’s father lay sleepless staring at the crumbling ceiling. His senses waited for the familiar smell and caring voice of Amrita. He did not know exactly what he was waiting for. His thoughts were engaged to the past, historical, irrelevant and obsolete. A clumsy group of people were hustling to protect a child and take him out to a safe distance from the spot. The nurse could immediately recognize the child. He was Amrita’s son.

Hurrying, she reached the spot and saw Amrita being run-over by some heavy vehicle. She lay smashed, scattered and spot dead in a pool of fresh blood. The shocked nurse could identify the white salwar suit that Amrita had planned to wear on that day on the occasion of her father’s eighty-ninth birthday. The nurse could identify Amrita’s detached arm full of glass bangles; the rainbow coloured bangles broken shattered and scattered. A tiffin carrier lay open and distorted a few feet away from her stretched arm. The special Kashmiri fried rice, her papa’s favourite, lay scattered like delicate petals of white flowers on the blood smeared dirty road.

That night Amrita’s papa became restless during his mealtime. He spat out the food and threw away the feeding spoon snatching it from the nurse’s hand. His restless eyes continued to search for the concerned and promising voice of his daughter who every day came to feed him.

His presence in the world remained like a hallucination thriving to establish an ancient period of history; present evaded him completely and left him like a relic among the mystery and stillness of the olden days. He remained half-awakened like fleecy mists through which a blurred vision of the far-off plains and hill ranges are indistinctly visible.

His favourite Simmons public library along with his soulmate countryhouse also evaded him. Perhaps the intricate designs of the wrought iron balustrade traced his fizzy mind as rainbow braces the rainwashed sky. He even forgot to miss the open sky of his countryland and considered the flaky walls as something imposing on him. He sometimes uttered broken split lines from verses.

© Kakoli Ghosh

Published in FERRING LOVE, an anthology edited by Nupur Basu. https://www.amazon.in/dp/B097S38QBS/ref=cm_sw_r_wa_apa_glt_fabc_4F7CFK6MH379DFCR7CKH